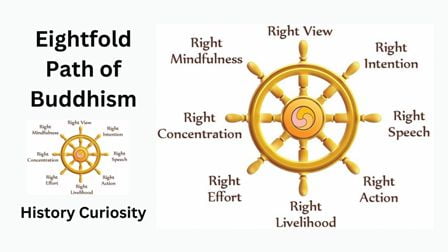

The Eightfold Path is a fundamental concept in Buddhism and serves as a guide that guides the individual to enlightenment and freedom from suffering. It consists of eight interrelated principles:

Right View: It begins with a deep understanding of the Four Noble Truths, recognizing the nature of suffering and the way to end it.

Right Intention: Encourages developing healthy intentions and aligning thoughts and actions with the pursuit of truth, compassion, and wisdom.

Right speech emphasizes truthful, kind, and constructive communication while avoiding lies, backbiting, and abusive language.

Right Conduct: Promotes ethical behavior and responsible behavior, refraining from harm, violence, and unhealthy behavior.

Right Livelihood: encourages the choice of a profession that does not harm others and is in accordance with Buddhist principles; promotes honest and compassionate living.

Right Effort: It involves diligently cultivating positive qualities and eradicating negative ones through mindfulness and determination.

Right Mindfulness: Promotes awareness of the present moment, observing thoughts, feelings, and sensations without attachment or aversion.

Right Concentration: Refers to the practice of meditation to develop focused and calm states of mind, ultimately leading to deep insight and spiritual awakening.

The Eightfold Path is a practical blueprint for individuals who want to overcome suffering, achieve wisdom, and reach nirvana, the ultimate goal of Buddhist practice.

The Eightfold Path is a fundamental concept in Buddhism

| Historical Facts | Eightfold Path of Buddhism |

| Perfect vision | Samyag Dresti |

| Perfect emotion | Samyak Sankalpa |

| Perfect speech | Samma Vaca |

| Perfect action | Samma Kammanta |

| Perfect meditation | Samma Samadhi |

Introduction

The Eightfold Path, Pali Attangika Magga, Sanskrit Astangika-marga, is an early formulation of the path to enlightenment in Buddhism. The idea of the Eightfold Path appears in what is believed to be the first sermon given by the founder of Buddhism, Siddhartha Gautama, known as the Buddha, after his enlightenment.

There he takes the middle path, the Eightfold Path, between the extremes of austerity and sensual indulgence. Like the Sanskrit term Chatvari-Arya-satanic, which is usually translated as the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism, the term Astangika-marga also implies nobility and is often translated as “The Noble Eightfold Path.”. Just as what is noble about the Four Noble Truths is not the truths themselves, but those who understand them, what is noble about the Noble Eightfold Path is not the path itself, but those who follow it.

Thus, Astangika-marga could be more accurately translated as “the eightfold path of the (spiritually) noble”. Later in the sermon, the Buddha expounds the Four Noble Truths and identifies the fourth truth, the truth of the path, with the Eightfold Path. Each element of the journey is also discussed at length in other texts.

An eight-part trail

Briefly, the eight elements of the journey are:

- 1. The correct view and accurate understanding of the nature of things, specifically the Four Noble Truths,

- 2. Right intention: avoiding thoughts of attachment, hatred, and harmful intentions,

- 3. Correct speech, refraining from verbal offenses such as lying, divisive speech, rude speech, and meaningless speech,

- 4. Good conduct, refraining from physical offenses such as killing, stealing, and sexual misconduct,

- 5. Live properly and avoid trades that directly or indirectly harm others, such as the sale of slaves, weapons, animals for slaughter, narcotics, or poisons.

- 6. Rieffort: abandoning negative states of mind that have already arisen, preventing negative states that are yet to arise, and maintaining positive states that have already arisen.

- 7. Proper mindfulness, awareness of the body, feelings, thoughts, and phenomena (components of the existing world),

- 8. Proper concentration and purposefulness

1. Perfect Vision, Right View, Samyang Dresti / Samma Ditthi

The word samyag means whole, complete, or perfect. Dosti means look; in Indian culture, it is a word used for any philosophy or belief; it is all opinions. Attitudes either help or hinder spiritual growth. This is the Buddhist criteria for their “rightness.”

We can underestimate the powerful influence the opinions we hold have on our lives. If we firmly believe that we are useless and cannot meditate, our attempts at meditation will be seriously hampered. Perfect vision is the wisdom part of the Eightfold Path and is followed by the rest of the path’s ethics and meditation.

However, wisdom is also the culmination of the triple path (ethics, meditation, and then wisdom). If we see the Eightfold Path repeating itself at deeper and deeper levels of realization, we can see the right view at different levels. As a right view, this part of the path is the initial, mostly conceptual view that leads us to practice the other seven parts.

These in turn deepen our understanding, and so on in a spiral that culminates in direct intuition or a perfect vision of the true nature of things. Here are some useful insights:

(i) Actions have consequences, or karma. This is an aspect of the basic view of conditionality. All experience arises depending on the conditions. If we live by this view, we will act skillfully by following the way things are and suffering less. We act kindly because it has an effect, and we meditate because it has an effect. This doesn’t require rocket science, just honest observation of our actions and appreciation of the quality of our experiences!

(ii) 3 marks of conditional or composite experience. All things are impermanent, devoid of any substantial substance, and unsatisfactory.

(iii) 4 Noble Truths

We deepen the right views into a direct, perfect vision through the three levels of wisdom. Learning, reflection, and meditative contemplation are dependent on conditions, or “put together.” They are impermanent, without any.

- (a) hearing or shruta-mayi-prajna: knowledge based on ‘hearing’, learning, and understanding learning clearly at a conceptual level.

- (b) reflection, or china-may-prajna: cognition based on thought; think about what we know. This is the stage where we appropriate the Dharma, making connections and realizing their consequences.

- (c) meditation, or Bhavana-may-prajna—knowledge based on meditation; this is the direct contemplation of the Dharma and its realization on a deeper and more complete level than merely conceptual.

2. Perfect Emotion, Right Intention, Samjak Sankalpa and Samma Sankappa

This limb is often translated as ‘thought’ but the word Samkappa is better understood as intention, purpose, plan, or will. Sangharakshita uses the word “emotion.” It is motivation to practice, orienting our will and emotions to the positive. Nice ideas and views won’t move us much if our motivations and desires firmly steer us in a different direction.

We must want to practice Buddhism; we must find the emotional equivalent of our intellectual understanding. Greed, hatred, and delusion sit at the heart of unawakened experience and prevent us from realizing bodhi, enlightenment.

While perfect vision works on delusion – the veil of concepts or views, perfect intention works on the veil of Kilesas – the tainted emotions of greed and hatred. Here are some right intentions or perfect emotions –

- (i) Reluctance, Surrender, or Satisfaction. This counteracts the greed, the insatiable desire to have and consume, that we indulge in in our society. The practice of contentment allows us to need less and brings a deeper and more enjoyable awareness of what we are truly experiencing.

- (ii) Hatred, goodwill, or metta. This is cultivated through the practice of mettà Bhavana, which combats hatred and reclaims the energy we waste in irritation.

- (iii) Not cruelty or harmlessness, ahimsa. This is one of the main emphases of Buddhism, embodied in the first ethical precept to refrain from harming living beings. It deepens through the practice of karuna bhavana, the cultivation of compassion, and our empathy with suffering beings.

- (iv) Generosity, the emanating emotion of connection with other beings through giving. This is the positive side of renunciation; our willingness to share possessions, time, and energy rather than clinging and hoarding everything for ourselves. We develop this emotion just by giving!

- (v) 4 Brahmavihara or heavenly abodes. They are the four basic positive emotions metta (goodwill), karuna (compassion), Mudita (sympathetic joy), and Upekkha (equanimity). There is a meditation practice on each of them. You will be familiar with metta bhavana, the others are the development of the deeper implications of metta.

- (vi) Sraddha, faith or trust. From a dharma perspective, it is trusting that our practice is working. It is an emotional attraction and reliance on goodness. Although it may be informed by intuition and reason, faith is ultimately valid only when we know it directly through our experience. Shraddha is deepened through devotional practices such as the sevenfold puja.

3. Perfect Speech / Samma Vaca

Buddhism sees man as threefold – body, speech, and mind – and gives us ways to examine the ethical implications of our actions at each of these levels. This part of the journey deals with speech. Our words are powerful – The Buddha spoke of our tongue as a double-edged ax that cuts both others and ourselves.

We cultivate perfect speech by developing a truer, kinder, more accommodating, and harmonious use of words. These qualities correspond to the 4 commandments of speech (part of the 10 commandments received at ordination to the WBO) – refraining from dishonesty; saying it as if it meant valuing what is true and speaking accordingly, not being ready to bend the facts to suit oneself or others.

Refraining from harsh speech; we speak to real beings with real feelings – kind speech considers our influence on others. Abstaining from recklessness; it’s not that we don’t have fun, it’s that we don’t drain our energy blabbering endless garbage. Life is short! Refraining from divisive speech; not to spread discord and gossip to divide people and instead use our words to promote harmony.

4. Perfect Action / Samma Kammanta

Perfect action is everyday life beyond our vision. Actions are considered skillful or unskillful (rather than abstractly good or bad) if they are motivated by generosity, love, and wisdom, or by their opposites, greed, hatred, and delusion if they are performed with regard to their consequences or not.

These five precepts are specific training that allows us to change our behavior from harmful to helpful in various areas of our lives. Traditionally they are presented in terms of abstinence from the unskilful, but Sangharakshita has put together positive correspondences emphasizing the skill towards which we are moving. Here are both lists –

- (i) I undergo the practice principle of refraining from harming living beings (purifying my body by acts of loving-kindness),

- (ii) I undergo the training principle of refraining from receiving what has not been given (with an open palm I cleanse my body generously),

- (iii) I undergo the training principle of refraining from sexually inappropriate behavior (I cleanse my body with calmness, simplicity, and contentment),

- (iv) I adopt the practice principle of refraining from false speech (I purify my speech by truthful communication),

- (v) I practice the training principle of abstaining from intoxicants that cloud the mind – (I purify my mind with pure and radiant mindfulness).

5. Perfect Livelihood / Samma Ajiva

Our work takes up a large part of our lives. Perfect living is about making this time part of our practice rather than an obstacle to finding a way of working that brings our awareness and kindness from our meditation deeper into our lives. It’s also about practicing our ideals in our social lives and becoming more responsible and creative with the impact we have on the wider world.

Traditionally, this is seen in terms of how we earn our living. The Buddha discourages people from trading weapons, “breathing things,” meat, alcohol, and poisons. In our complex, informed modern world, we can see the implications of living well in our effects on the global economy and environment (is it ethical to drive a large fuel-guzzling vehicle?) and in the effects of our purchasing of fair trade, environmentally friendly products. , etc.

In ancient India, the average person had little political influence; the only social effect they had control over was trade. Today we live in a different world. We are deeply involved in our society, whether we like it or not, and we are aware of the impacts we have, so this part of the journey has implications for us in our political and social lives, the ethical dimension of voting, representation, and the possibility of involvement in projects for the environment and social change.

One of the developments in Buddhism in recent years has been the growth of engaged Buddhism, where some modern Buddhists have taken the view that it is not enough to sit with their eyes closed and wish for nice thoughts and have become actively involved in non-violent campaigns against such issues as global poverty, deforestation, and human rights.

6. Perfect Effort / Samma Vayama

The Buddhist path is active; Despite modern Western notions of a laid-back Buddha, practicing the dharma requires consistent effort. The Buddha constantly exhorted his followers to strive to overcome what held them back from fulfillment. Effort is involved throughout the journey; energy is required to exercise any of the eight limbs. It is also preserved and created by their practice – for example, deepening our positive emotions prompts us to do good and stops our energy from escaping into empty desire and hatred. The Four Right Efforts detail this:

(i) Prevention

The effort is required to stop the emergence of new unhelpful mental states.

(ii) Eradication

Removing already existing useless states. (The five hindrances are a good summary of these hindrances, although they are usually studied in relation to meditation, they apply to our general life. They sense desire, ill will, restlessness, anxiety, laziness, and rigidity, doubt, and indecision.)

(iii) Development

Cultivating helpful, positive mental states such as loving-kindness, generosity, calmness, simplicity and contentment, mindfulness, etc.

(iv) Maintenance

Efforts to support and encourage already established auxiliary states.

These four endeavors can be likened to gardening. First, you prevent any new weeds from growing and remove any nasty established weeds., dig down to the roots to prevent them from re-sprouting.

Then you plant the beautiful roses and cabbages you desire and keep them growing and blooming. Balanced effort is sustainable, steady effort, the Buddha likened it to a well-strung veena (lute), if the strings are too loose or too tight, it sounds terrible. Similarly, if we put in too little effort or too much in a way that does not come from our depths, our spiritual practice is “off”.

We need to balance the joy of the positive qualities we already have and want to keep, with the determination to develop new qualities and to prevent and eradicate the negative ones. Otherwise, we can either be discouraged or dull and statically satisfied.

7. Perfect Knowledge / Samma Sati

Mindfulness, or mindfulness, is a fundamental virtue espoused throughout the Buddhist tradition, from the Anapanasati (watchful breathing) of Theravada Buddhism to the tea ceremony of Japanese Zen Buddhism. Developing mindfulness is a basic meditative practice of gathering and focusing our attention until we become fully present and truly experience our life and what is happening in it. This state, called immortal inattention, is dead to life.

Mindfulness has an ethical quality in that it is about knowing what is skillful and what is unskillful and remembering the consequences of actions. It also has an aesthetic quality—we can be aware of our world and appreciate it for its own sake, grasping it on a level beyond the petty, understanding mind that sees things in terms of self-centered utility. The four mindfulness are found in the Anapanasati and Satipatthana Suttas of the Pali Canon, the classic texts on the practice—

(i) Mindfulness of the body

To know what our body is doing, to be in our ‘pieces’. Mindfulness of breathing is an obvious practice for this, a touch as well as a body scan.

(ii) Mindfulness of feelings

Being aware of our response to people, things, and thoughts; are we satisfied, dissatisfied, or indifferent?

(iii) Mindfulness of states of mind

To be in touch with the quality of our mind and heart at all times.

(iv) Mindfulness of phenomena or objects of the mind

Knowing what our mind focuses on and what it “holds on to”.

Sangharakshita in Vision and Transformation presents a similar list –

- (i) Things: Noticing and appreciating the infinite, elusive beauty of each cornflake in the morning!

- (ii) Self in three dimensions: mindfulness of body, feelings, and thoughts (see above).

- (iii) People: metta bhavana is the practice of being aware of people. It’s about learning to see people as other people, to feel and perceive as we do and not as objects.

- (iv) Reality: to see into the depths of the world around us and to be aware of its deepest implications. We can think about the qualities of the Buddha or one of his teachings until those qualities and truths sink in deep enough to see them permeate the world around us.

Mindfulness takes time. We have to slow down enough to notice things. Take the time to look and enter an immortal moment of awareness!

8. Perfect Meditation / Samma Samadhi

The word samadhi means to be firmly fixed or steady, in this case, the mind is wholeheartedly fixed or steady in meditation. There are different levels of samadhi; either mundane concentration on an object or establishment in an enlightened state of consciousness. There are expressions for these different depths.

(a) Samatha

The experience of stillness as the mind becomes increasingly settled, integrated, and absorbed in the object of concentration. This growing integration is described in the four dhyana of form and the four dhyana of formlessness (dhyana in Sanskrit). Dhyanic states are characterized by concentration factors –

(i) Initial thought

A clear thought related to meditation

(ii) Sustained thinking

Thinking consecutively in a directed manner.

(iii) Rapture

The release of energy in the form of pleasant physical thrills flows through the meditator’s body.

(iv) Bliss

The vast experience of refined pleasure arising from contentment

(v) One-pointedness

The main quality of integration in our meditation is that is fully focused.

(b) Samapatti

Attainment or sign – profound and unusual sights, sounds, or bodily sensations that arise as a sign of concentration.

(c) Self-samadhi

Settling in enlightened consciousness, described in traditional Buddhism as the three samadhis –

(i) Formless

Perfect freedom from all thoughts, in the sense of not being bound by concepts and thus able to see reality directly,

(ii) Directionless

Not being pulled in any direction because it is no longer attracted or repelled by anything at all,

(iii) Emptiness

Complete awareness of the lack of anything substantial.

Conclusion

The Eightfold Path is discussed less than the Four Noble Truths in Buddhist literature. In later formulations, the eight elements are depicted not so much as precepts for behavior but as qualities that are present in the mind of one who has realized nirvana, the state of cessation of suffering, and the goal of Buddhism.

(FAQ) Questions and Answers about the Eightfold Path of Buddhism

Q-1. What is the eightfold path of Buddhism?

Ans. Right understanding (Samma Dhiti)

Right thought (Samma sankappa)

Right speech (Samma vaca)

Right action (Samma kammanta)

Right livelihood (Samma ajiva)

Right effort (Samma vayama)

Right mindfulness (Samma sati)

Right concentration (Samma samadhi)

Q-2. What is the name of the eightfold path in Buddhist literature?

Ans. Ashtangika Marg.

Q-3. Ashtangika Marg is associated with which religion?

Ans. The word Ashtanga Marga is associated with Buddhism.

Q-4. Who ordered the observance of the Eightfold Path?

Ans. Gautama Buddha enjoined the observance of the Eightfold Path