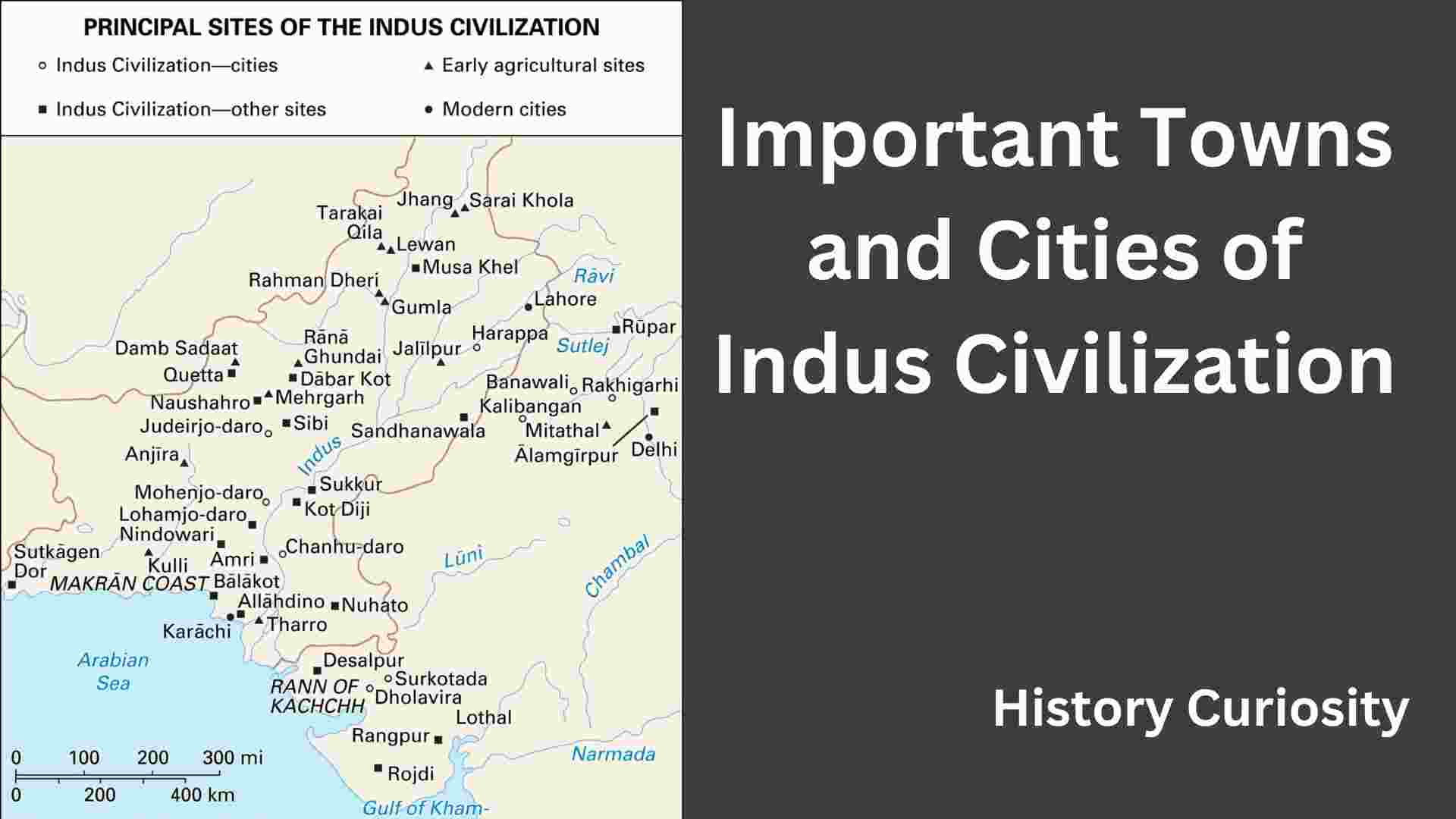

Explore the ancient wonders of the Indus civilization through its important cities. Discover the rich history of Harappa, known for its advanced urban planning and intricate architecture. Mohenjo-Daro, another prominent city, showcases the sophisticated sewage and drainage systems of the Indus people. Lothal, a coastal city, reveals its naval skills with a well-planned shipyard. Enter Dholavira, where you can witness a remarkable water management system and unique reservoirs. A major archaeological site, Kalibangan, reveals insights into Indus script and culture. Explore the Rakhigarhi Trade Center, which sheds light on their business activities. These ancient sites provide glimpses of a highly organized and technologically advanced civilization that flourished more than 4,000 years ago. Immerse yourself in the mysteries and wonders of the towns and cities of the Indus Civilization on your journey back in time.

Important Towns and Cities of Indus Civilization

| Historical Topic | Important Cities of Indus Civilization |

| Harappa | River Ravi |

| Mohenjo Daro | Indus River |

| Lothal | Bhogava River |

| Suktagendor | Dasht River |

| Kuntasi | Bhadra River |

| Desalpur | Bhadar River |

| Kunal | River Saraswati |

Introduction Important cities and towns of the Indus Civilization

The excavated Indus cities can be divided into the following groups for their convenient description:

- (A) Nucleus cities

- (B) Coastal cities and ports

- (C) Other cities and towns

- (A) Nucleus cities

The three largest settlements—Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, and Dholavira—were the capitals of the Indus Civilization.

(A) Nucleus cities

(i) Harappa

(a) Relics of the Indus Valley Civilization were first discovered and excavated in 1921 by D. R. Sahni. The site has two large and impressive ruins located about 25 km southwest of the district town of Montgomery in Punjab (Pakistan) on the left bank of the Ravi River. The western mound of Harappa, smaller in size, represented a citadel, a parallelogram in plan 420 m from north to south and 196 m from east to west; it was 13.7–15.2 m high. The citadel wall was reinforced in places with bastions. The burnt brick buildings that stood on the platforms inside the citadel were built six times in a row. Outside the citadel at Harappa (Vats, 1940; Wheeler, 1962), an area of 275 m2 contained some important structures identified as workers’ quarters, work floors, and granaries.

(b) The workers’ quarters, ten small oblong dwellings located near the northwest corner tower of the citadel, were uniform in size and space (17 x 7 m2) near these workers’ quarters were 16 pear-shaped ovens. plan with cow ash and charcoal. A crucible used for melting bronze was also found at a slightly higher level. The granary objects lay 32 m apart with a group of objects measuring 15.24 x 6.10 m arranged symmetrically in two rows of six with a central passage 7 m wide. A rammed earth platform was riveted on the east and west sides. On the south side of the granaries lay the working floors, consisting of rows of circular brick platforms intended for threshing grain, as the cracks in the floors contained wheat and barley.

(c) The location of Harappa has led several authors to conclude that it was a “gateway city” at the edge of the Harappan region and marked the meeting point of the routes coming from Gomal and other passes leading to the Iranian plateau. In this sense, Harappa formed the main link between the core territory and the peripheral region or the outside world. Apart from the presence of sixteen ovens on Mound F, no other production sites have been found, proving that it functioned as a “gateway city”.

(d) The evidence of the disposal of the dead at Harappa is quite interesting. These were found south of the citadel area named Century R 37. The excavation also yielded 57 burials of various types. The skeletons were deposited in pits cut in the ground along with grave goods. There is also evidence of mud brick lining around the grave. Bronze mirrors were found in 12 graves; in one was an antimony rod, in another a ladle, and in several others, stone blades were found.

(e) The remains of material discovered at Harappa are typically Indus in character and include pottery, horn blades, copper and bronze implements, terracotta figurines and seals, and sealers. From Harappa 891, seals were discovered that made up 29.7 percent of the total writing material of the Indus Civilization. It also yielded two interesting stone sculptures not available at any other Indus site. Both statues have drilled sockets for dowels to attach the head to the limbs, a technique not found in later statues. The first figure is a small nude male torso made of red sandstone (height 9.3 cm) with an overhanging abdomen. According to Marshall, the main quality lies in its “refined and amazingly true modeling of fleshy parts”. This figure has been identified by some as a prototype Jina or Yaksha figure. The second male figure (10 cm) is made of gray stone and is in a dancing pose (with twisted shoulders and one raised leg). A dowel was used to attach the now missing head. Marshall identified her with a much later icon of Shiva as Nataraja, lord of the dance. However, some scholars have identified it as a female statue.

(f) Other important finds at Harappa include a well-preserved brick-built water tank with a narrow covered channel, an ivory seal and a clever combination of three copper implements joined together by looped ends. They are an awl with a sharp point, a double-edged knife, and forceps, which may be intended for surgical instruments.

(ii) Mohenjodaro

(a) The site of Mohenjo Daro (literally mound of the dead), located in the Larkana district of Sindh (Pakistan), about 483 km south of Harappa, also has two mounds. The western low mound was the citadel (200 m x 400 m) and the eastern extensive mound held the relics of the buried lower city (400 x 800 m). The former is crowned by a stupa of Buddhism built in the 2nd century BC The mounds were excavated by R. D. Banerjee (1922), Sir John Marshall (1922-30), E. J. H. Mackay (1927-1931), S. M. Wheeler (1930-1947), and G. F. Dales (1964–1966) and yielded seven successful levels of construction phases, in addition to many relics related to the Indus Civilization. It was the largest city of the civilization and was celebrated along with Harappa as the capital of this vast state. However, there is no positive evidence that the cities were capitals, either of separate states or a unified empire. It has also been postulated that Mohenjo-daro was the capital of a vast empire with Harappa and Kalibangan as its “subsidiary centers”. Both of these conclusions are inferential and hypothetical at best.

(b) Mohenjodar’s most famous building is the Great Baths. Located in the area of the citadel (6 m in the south and 12 m in the north) it is an example of beautiful brickwork. It is a rectangular tank and measures 11.88 m from north to south, 7.01 m wide and 2.43 m deep. It had stairs on the north and south sides that led to the bottom of the tank. To make it waterproof, swan bricks (burnt bricks) were set at the edges in gypsum mortar with a layer of bituminous mastic inserted between the inner and outer skins of the bricks. Also, the staircase was originally finished with a wooden tread embedded in bitumen. Water for the bath was provided by a well in the next room. The outlet with an arched drainage channel on the west side of the embankment was intended for occasional emptying. Both surrounded a portico and sets of rooms, while a staircase led to the upper floor. Some researchers believe that the rooms were “provided to members of a sort of priesthood” who lived in them and came down at stated hours to perform the prescribed ablutions, while others believe that the rooms were intended for changing clothes. However, there was general agreement that both must have had a religious function.

(c) To the west of the Great Bath is a group of twenty-seven blocks of brickwork, which are criss-crossed by narrow ventilation ducts. Wheeler interpreted this structure as the stage of a large granary (similar to that of Harappan, but with a different design). Allchins, however, took a different view. According to them, it has some civic function, probably associated with religious rituals. This structure measured 45.72 m from east to west and 22.86 m from north to south. It was built before the construction of the Great Bath, but its construction continued as several additions were subsequently added to it. To the north and east of the Great Bath, a long building is believed to be “the residence of a very high official, perhaps the High Priest himself, or perhaps a dormitory of priests”. It has a 10 square meter open yard. Remains of a building (27.43 m2) divided from east to west into five aisles by 20 brick pillars arranged in four rows of five, originally provided with long low benches of perishable material, as indicated by the floor “divided by some narrow passages or lanes neatly paved with bricks ” reminds us of the Achaemenian apadana or audience hall. A seated male stone statue was discovered in a complex of rooms immediately to the west of this chamber, near a series of large worked stone rings, possibly pieces of architectural masonry but more likely part of a ritual stone column, was also seen. These finds, according to Allchins, resemble those associated with the alleged temple in the lower city and indicate the presence of a temple in this part of the citadel. The lower city of Mohenjo Daro, which like Harappa does not appear to have been fortified, showed all the elements of a planned city. Its plan appears to have resembled a grid of main streets running north-south and east-west, dividing the area into roughly equal-sized and roughly rectangular blocks, 800 feet from east to west and 1,200 feet from north to south.

(d) The main streets in the lower part of Mohenjo-daro are about 9.14 m wide. Lanes (3 m wide) divide the blocks instead of main streets, on which “prison-like houses opened their secret doors”. Brick drains, however, “have no analogs in pre-classical times, and nobody approaches them in today’s non-Western Orient”. Houses lacked decoration in general but were provided with grilles or window screens made of terracotta.

(e) “Notable and recurring features are the insistence on water supply, bathing, and drainage, together with a prominent staircase to the upper floor. Some houses have a western-type sit-down latrine on the ground or first.” floor with a sloping and sometimes stepped channel through the wall to a pottery or brick drain in the street outside.”

(f) From other material remains it is clear that Mohenjodaro was a great city of the Indus Civilization. About 1,398 seals discovered from this site constitute 56.67 percent of the total written material of the Indus cities. The discovery of some stone, bronze, and terracotta figurines testifies to the level of aesthetic sensibility of the citizens. Several copper and bronze vessels and a large amount of pottery have been recovered from Mohenjodar. The depictions on the seals shed light on animal sacrifices, the cult of the mother goddess, the worship of animals and trees, and the belief in the Shiva-Pashupati protoform.

(g) Some other important monuments of this civilization are: the depiction of a ship on a stone seal; a carved stone representation of a riverboat; depiction of a ship on a terracotta amulet; terracotta cart; copper and bronze tools and vessels; limestone sculpture of a bearded head (19 cm); compound animal, a bull with an elephant’s trunk and ram’s horns; a toy bull with a moving head; another depiction of a composite animal with bull, elephant and tiger features on the seal; stone lingam; terracotta seated female figure, perhaps making dough (also at Harappa and Chauhundaro); terracotta monkey with hole punched to insert climbing line (3.5 cm); stone ram of uncertain provenance, maximum length 49 cm and height 27 cm (probably the largest and best-preserved item in the entire repertoire of Harappan sculpture); small figurine of a sitting squirrel in faience (2.3 cm); Indian rhinoceros steatite seal; female figurines nursing their babies (also at Harappa); female figure carrying bread in hand (also at Harappa and Chanhudar); double-faced human figures; A tiger with a human face (also at Harappa); anthropomorphic head with beard on body of dog; a figure of a pregnant woman with a cat’s head (a figure of a cat with a human body was found in Harappa); human figure with fox head; two masks displaying bull horns; two-headed animal on a pin, etc.

(iii) Dholavira

(a) Today, a modest village in Bhachau taluka of Kutch district in Gujarat, Dholavira is the latest and one of the two largest Harappan settlements in India, the other being Rakhigarhi in Haryana, and may be the fourth in the subcontinent, after Mohenjo Daro in Sindh, Ganeriwala in Bahawalpur, and Harappa in Punjab (all in Pakistan) in terms of area or coverage, if not status or hierarchy. Flanked by the Mandsar and Manhar storm currents, the ruins of this Indus settlement, locally known as ‘Kotada’, are located in Khadir, a largely isolated island in the Great Rann of Kutch with an enclosed area of 47 hectares.

(b) The ancient mounds of Dholavira were first explored by J.P. Joshi of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), but extensive excavations were carried out there in 1990–91 by a team of archaeologists led by R.S. Bisht of the ASI. Recent excavations at Dholavira have revealed the magnificent remains of another Harappan city, highlighted by massive proportions, intricate planning defined by elaborate fortifications, exquisite architecture, fine water structures, and a vast accumulation of successive settlements over more than a millennium.

(c) Although excavations are ongoing, very little has been published so far about all the excavations and the nature of the settlements. However, excavations have proven the existence of all three phases of the Harappan culture. According to Allchins, it is not yet clear whether the earlier occupation should be classified as early Harappan or as a local culture.

(d) Dholavira has many unique features not found in any other Harappan site. Unlike other Harappan cities, which were divided into two parts, the “citadel” and the lower city, Dholavira was divided into three main divisions, two of which were heavily protected by rectangular fortifications. No other website has such a sophisticated structure. But this may have been because “there was no precedent for such a common peripheral enclosure arrangement involving walled or unwalled (sic) parts of an Indus settlement elsewhere.” Nor does it compare to the vast open areas 70 to 140 m wide that connect the outer and inner defensive walls, especially at strategic locations in Dholavira. So there was also an inner cover. There were two The first inner enclosure was lined in the citadel (acropolis), where the supreme authority probably resided.

(e) The rectangular main site is surrounded by a rubble and mud brick wall, about 700 m from east to west and 600 m from north to south. On the eastern side is the Lower Town. To the west is a square area (Middle Town) about 300 m long, and to the south it is adjoined by two smaller square walls known as the ‘castle’ and the ‘forecastle’. The middle city (madhyama) was intended for the relatives of the supreme authority and the administrative navy. This city in the middle is exclusive to Dholavira – none of the other Harappan sites have it. So much so that it is generally regarded as the contribution of the Rigvedic Aryans to city planning. The “castle” is described as standing to a maximum height of 16 meters, surrounded by stone ramparts with adobe infill, measuring around 140–120 m. The “Bailey” is also described similarly. The Allchins are quite skeptical about accepting the proposed defensive nature of the ‘castle’ and ‘bailey’. According to them, if and when these features are more extensively excavated, they will be found to be closer to the citadel complex at Kalibangan, for which a religious function is generally accepted. The structural funds from Dholavira include some fine ashlar masonry slabs, stone pillar bases, and steps of a quality not known from any other Harappan site. There are also reports of impressive water and drainage structures.

(f) Other important material finds recorded from Dholavira are the remains of a horse, many copper objects including a bronze animal figurine, evidence of copper working, beadwork, and other craft activities. Some typical Harappan seals, some with inscriptions, were also found. Another extraordinary find is a Harappan inscription with nine letters, each 37 cm long and 27 cm wide, composed of inland cut pieces of milky white matter. This inscription was found on the ground under one of the gates of the outer fortifications. Excavator R. S. Bisht thinks that the inscription was originally mounted on a sort of slab above the gate and “may have been intended for public reading”. But all such opinions will have to wait for confirmation until someone cracks the script. Access to these fortified settlements in Dholavira was secured through an elaborate gate complex, equipped with possible guard rooms. Behind the northern gate in the Central Zone of the citadel is a 12.80 m wide water reservoir equipped with a 24 m long and 70 m wide inlet channel to drain rainwater, which is so rare in this semi-arid environment. The discovery of the only stadium known to the Harappans is another unique feature of Dholavira. The entrance to this stadium was from the “castle” and “bailey” section. In addition, a stone sculpture of a mongoose (37 cm) was also found,

(g) Exploring Dholavira is like opening a whole book on Indus. We now have answers to some of civilization’s most enduring riddles. Dholavira’s findings change many existing ideas. The place must have been a small but strong fortress 5,000 years ago. Later, in the middle of the third millennium BC, it became a large and prosperous city, a model trading center. High walls surrounded the 50-hectare city. The presence of a citadel, a middle city, a lower city, and an annex indicated a highly stratified society.

(h) But most surprising are the giant tanks (the largest measuring 80.4 meters by 12 meters and 7.5 meters deep) which contain an astonishing 2,50,000 cubic meters of water. The Dholaviras knew the art of saving water. The Dholavirani built check dams and collected water in reservoirs. Enough water was collected to meet the city’s water requirements. These tanks were connected to wells, which in turn filled cisterns for drinking and bathing. But it wasn’t just water management skills that made the city unique.

(i) There is much more to a megapolis. Excavations in the cemetery lying west of the town yielded a number of burial structures that are still typical of Dholavira. The burials clearly indicated that the inhabitants believed in an afterlife. It also demonstrated the presence of a number of ethnic groups, each with their own distinctive customs indicating a thriving trading community, attracting people from all over.

(iv) Rakhigarhi

(a) Three years of excavations at Rakhigarhi in the Hisar district of Haryana have revealed another Harappan city with a Harappan core that may have been a provincial capital of the Harappan civilization. The excavation, which has been carried out by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) since December 1997, has revealed some important results. This will give us an opportunity to assess its potential as a provincial capital of Harappan days. During the excavations, two distinct cultures were identified – Early Harappan and Mature Harappan. Located on the plains of the ancient Drishadvati River, the excavation site happens to be “one of the largest Harappan sites” at 230 hectares, next to Mohenjo Daro.

b) On the question of the possibility of identifying the capital of a province of the Harappan civilization that had a flourishing trade, among the investigated Harappan sites in the Saraswati-Drishadvati valley, Rakhigarhi seems to be the largest, and thus perhaps deserves the status of a provincial capital of the eastern extension of Harappan hegemony. The discovery of circular structures at the entrance of the valley, a unique feature of the early Harappan days, has also been reported. The structures are bordered by two or three layers of mud bricks with spaced post holes. Mature Harappa, a period of urbanism characterized by fortified settlements, writing, and the use of standardized weights and measures, has been traced to the site. Evidence of the adobe structure of granaries divided into cubicles indicates the overproduction of food grains and storage systems. The site also provided samples of barley, wheat, and rice.

(c) The dead were buried in a long pit in a north-south orientation. Graves usually consisted of pots kept behind the head of the dead. Several of the buried women also had shell bracelets on their left hands, while one had a miniature model of a fillet in gold.

(B) Coastal cities and ports

Several towns of the Indus civilization developed on the coast of the Arabian Sea, which functioned as ports. Notable ones included Suktagendor, Balakot, and Allah Dino. Likewise, Lothal located in Kutch was connected to the sea by the river Bhagavo.

(i) Suktagendor

a) Suktagendor, located at a distance of 56.32 km from the coast of the Arabian Sea and about 500 km west of Karachi, on the banks of the Dasht River near the border with Iran, was an important center of the Indus Civilization discovered by Sir Aurel Stein in 1931. According to Dales, it was Suktagendor originally a port that was later cut off from the sea due to coastal uplift. However, some other scholars believe that it was a riverside trading post located in a separate cultural area, as the Baluchistan highlands appear to be outside the Harappan zone. R.H. Dyson thinks it was a military base. According to Shashi Asthana, Suktagendor was associated with the distribution of trade items. It was established to send shipments in various directions, especially to West Asia.

(b) The fortifications here measured 150 m from north to south and 110 m from east to west. It was built of rough square stone blocks set with clay. It has a 2.5 m wide entrance flanked by massive rectangular bastions at the western end of the southern side. Subsequent work on the site by Dales (1962) revealed a dual division of the township into ‘Citadel’ and ‘Lower Town’. The citadel was fortified with a wall 7.62 m wide, which was supplemented inside with a platform made of mud bricks.

(ii) Balakot

(a) Between the coastal sites of Balakot, situated near the center of the Khurkera alluvial plain on the south-eastern side of the Las Bela valley (on the old coast, about 20 km from Las Bela town) and Somany Bay about 98 km north-west of Karachi, proved to be an important settlement providing remains of pre-Hindu and Indian civilization. Here the mounds lie a short distance from the modern sea coast and doubtless were even nearer in ancient times. Excavated in 1963-79 by George F. Dales (1979), these mounds rise to a height of about 9.70 m from the earth’s plain and cover an area of approximately 18 x 144 m (or 2.80 hectares). Four radiocarbon dates for the upper levels give calibrated dates between 4000 and 2900 BC. Many structures were found here, such as walls, pavements, and small platforms made of mud bricks (10x20x40 cm) belonging to the oldest phase. Dales noted that there is a sense of continuity running through the period, while the break before the reconstruction of the settlement in mature Harappan times is equally clear. Dyson thinks it was a colonial site where mature Harappan control was superimposed over a local indigenous, non-Harappan culture.

(b) Excavations revealed that there was a broad east-west lane almost bisecting the area at right angles with two smaller lanes. Mud bricks were the standard building material, although a few canals were also lined with kiln-fired bricks. “There is some evidence of thin plastering of the floors, but this was not done as usual practice. Structures for which we have not yet defined complete plans were equipped with hearths, usually accompanied by one or two storage vessels placed close together.” on the floor. There is at least one intact example of a bathroom with a toilet with a ceramic bath, a fireplace, a buried water tank, and a drain from broken pots.’

(c) Excavations have also revealed Balakot and other coastal sites of Lothal. Nageshwar and Kuntasi were what can be called ‘resource centers’, obtaining shells and other raw materials, either locally or from further afield, and having local workshops for the manufacture of bangles and other decorative items (Allchins, 1997). It was a major center of the shell industry.

(iii) Allahdina

(a) Allahdino is located approximately 16 km east-northeast of the confluence of the Indus and the Arabian Sea and about 40 km east of Karachi, Pakistan. Excavations at Allahdino were carried out by W. A. Fairservice with the aim of getting to know in detail the inner character of the Harappan civilization as well as the relationship between large cities and small settlements.

b) After three and a half seasons of work, the archaeologist managed to obtain an impressive amount of material: more than 300,000 sherds, 24,000 bicones, 2,600 terracotta triangles, 1,500 bracelets, and 196 pieces of copper. In summary, excavations have demonstrated the presence of almost all major categories of artifacts of the mature Harappan culture, including silver, gold, and semi-precious stones. At the same time, there is no evidence to suggest that any of these objects, including ceramics, were produced locally. Quite obviously, these objects were brought by its inhabitants who participated in the Harappan inland trade network. Shashi Asthana calls it a “distribution center” as opposed to a “production center”.

(c) Excavations have yielded the remains of structures built of mud bricks and stone, coated with clay plaster. The foundations of the great walls, pavement drains, etc., were of stone masonry. The buildings here have a square or rectangular shape, divided into several sections with an apparent regularity visible both inside and below the architectural whole. Stone walls have also been found that have small holes. In one of the rooms of Building VII, a small pot was found at the site containing the hoard known as the Allahadino Jewelry Hoard, one of only five major hoards to be discovered from the entire Indus region. The owner must have been rich and therefore influential. The finds of this hoard included a massive belt or necklace of 36 long carnelian beads and bronze spacer beads. Around this belt in the container were stuffed two or three multi-strand silver bead necklaces, eight silver bead coins, fifteen agate beads, a copper covered with gold foil, and a collection of twenty beaded gold nuggets and ornaments that were folded. preparation for remelting. One silver necklace was made of eight silver discs, each with three parallel perforations to accommodate several strands of small silver beads. This treasure is very similar to others found in Mohenjodar and Harappa. A hoard of silver ornaments including several fillets, a floral headdress, and carnelian beads from the Kunal site of the early Harappan phase was recently found.

(iv) Lothal

(a) Situated near Saragwala village about 80 km south-west of Ahmedabad in Dholka taluka in Gujarat in a level plain between the Bhogava and Sabarmati rivers at some 12 km away from the Gulf of Cambay, Lothal was an important trading and manufacturing center of the Indus civilization. The excavations at this site by S. R. Rao in 1954-62 brought to light five-period sequences of cultures.

(b) According to Rao, it is a “certainty that the Harappans came to Lothal for trade or colonization in 2450 BC” and that when the settlement was destroyed in the wake of a great deluge the people moved to Rangpur and Bhagatrav around 2000 BC. This argument of Rao is based on the supposed absence of Harappan sites in the tract between Sind and Lothal and the establishment of a relative chronology (Harappan chronology) that claims absolute priority in the region for the founding of Lothal. L. S. Leshnik has, however, questioned the dating, and further explorations of the Kutch area have brought to light a number of Harappan sites.

c) From the excavated remains of urban planning and other material equipment, Lothal, a medium-sized site, appears to be a mini Harappa or Mohenjo-Daro. However, Lothal seems to be better planned than Mohenjodaro in one respect. The streets of Lothal are straight and always run in cardinal directions. The site was almost rectangular with a longer axis running from north to south. It was surrounded by a massive brick wall to protect it from floods. The residential complex was divided into a citadel (Acropolis) and a residential quarter (Lower Town). The citadel or acropolis at Lothal, trapezoidal in plan, measures 117 m east to west, 136 m north, and 11 m south, contains a 3.5 m high mud-brick platform with the ruler’s abode (126 × 30 m) with drain and bath. Near the Acropolis stood the remains of a granary built on a brick platform (48.5 x 42.5 x 3.5 m) divided into 12 cubic blocks. It played a vital role in the economy of Lothal. On the southwest corner of the acropolis was a warehouse building, covering 1,930 m2 of floor space, on a 4 m high platform. There were other buildings on the raised platform. A series of 12 bathrooms and wastes were discovered here. A typical house had several rooms, a kitchen, and a front porch. There is also evidence of adobe, terracotta ball, or pellet paving.

(d) The lower town had a bazaar in the north and an industrial sector in the south. On Street 1 there were shops with two or three rooms, and occasionally there were merchants’ houses with four or five rooms. These houses were equipped with bathtubs, drains and later soaking tubs. The house of a rich merchant had three rooms and a courtyard, to which three rooms were later added. It consisted of large gold necklace beads, four steatite seals, shells, copper bracelets, and a beautifully painted clay vessel. Of this, the finding of axial tube gold beads and Reserved Slip Ware shards, associated with Sumerian origin, suggests that the traders engaged in foreign trade.

(e) Workshops of shell and copper workers were uncovered in the bazaar. On the west wing of the acropolis were eleven rooms of various sizes intended for a bead factory. “where several lapidaries worked together on a central platform and lived in rooms built around it”, covering an area of 500 m². Two clay vessels containing more than 600 gem beads in various stages of production were found here. On this basis, it is believed that Lothal along with other coastal sites like Balakot, Nageshwar, and Kuntasi were resource centers with local workshops for production.

(f) The finding of a seal from the Persian Gulf and Reserved Slip Ware suggests that Lothal was involved in the maritime activities of the Indus Civilization. Mention may be made of the most important burnt-brick structure at Lothal (214 x 36 x 4.5 m), identified as a “shipyard” by the excavator, which was connected by canals to the neighboring estuary. A spillway and shut-off device were installed to control the inflow of tidal water and enable automatic desilting of the canals. Several heavy pierced stones, similar to the modern anchor stones used by traditional seafaring communities of the western Indus (the shaduf system), were discovered at its edge. The river that flowed on the north side of Lothal was connected by a drain or nallah. In Rao’s view, part of the cosmopolitan Harappan population “could be identified with the pre-Rigvedic Aryans”.

(g) This interpretation has been challenged by Lawrence S. Leshnik on the grounds that, apart from the basin, there is very little about Lothal to help identify it as a trading partner of Ur and Susa. According to him, one seal of the Persian Gulf type, a seal impression, some bun-shaped copper ingots, and fragments of reserved ware, which are said to resemble seals from Ur, Brak, and elsewhere from Ra, hardly support the fact that the above ceramic type has now been recognized at several sites in Kutch, so it cannot be accepted as proof of unique contacts of Lothal with the West. Leshnik suggested that it was a reservoir for the intake of fresh water that was piped from higher ground inland to an area where the local water supply was ancient, as it is today, salty. Allchins (1997) outlined the difficulties in identifying the structure as a shipyard. According to them, the threshold of the main entrance to the dock is at such a level that it would appear that ships of even moderate draft could only enter when the surrounding water level was so high that it practically flooded the entire settlement. However, the interpretations of Rao and Leshnika still remain unproven.

(h) Another important discovery at the site was the cemetery, which was located on a slightly elevated terrain in the neighborhood of the dwelling. The area was very small and congested due to the lack of sufficiently flat, open, and dry land. Because of this, graves that overlap each other have been found and later burials have been truncated. Interestingly, a double burial was found here. Another important discovery from Lothal was the evidence of rice cultivation. We have documents for the peels in the form of prints on ceramics. However, it cannot be determined whether the rice was of the wild or cultivated variety. Rangpur is the only other place from where similar evidence has been discovered. Rao estimated the population of Lothal to be around 15,000, while Possehl, however, thinks it could be between one and two thousand. Lothal also issued 213 seals and seals.

(v) Kuntasi

(a) Kuntasi, located in western Saurashtra on the right bank of the Phulki River, has revealed a small port settlement of mature Harappans. The place was earlier reported as Hajnali but was later found to be in Kuntasi in Maliya Taluka of Rajkot district. It was first reported by late P. P. Pandya and later extensively studied by Y. M. Chitalwala. The mound was known locally as Bibi-no-Timbo.

(b) The settlement was divided into two parts, i.e. the fortified area and the dwellings outside it. The castle wall is made of large rough stones. It was nothing more than a small village. The evidence shows that the total number of people occupying the site must have been very small and engaged in occupations other than agriculture. The discovery of the anchor stone helps to identify it as a port. Here, Period I represents the mature phase dated to ca. 2200-1900 BC, and Period II of the Late Harappan is assigned to ca. 1900-1700 BC.

(c) The excavator found a total of four construction phases. The structures included interconnected spacious chambers, roads, gates, semi-circular stone platforms, and workshops. The workshop manager’s house is the most imposing structure in Kuntasi, consisting of several rooms, the front of which was very spacious. Adjoining it to the south was a granary containing five large pit silos. M. K. Dhavalikar identified this place as a center of handicrafts. Typical Harappan seals, some with inscriptions, have been found here. Craft activities included bead making, including long barrel carnelian beads, faience beads, steatite, lapis lazuli, shank, ivory bracelets, and perhaps copper smelting. Numerous furnaces and storage areas were also found. Nageshwar in western Maharashtra was another site where a garnet processing industry was discovered. The discovery of a cache of lapis beads at Kuntasi led Dhavalikar to believe that they were intended for export to the cities of Mesopotamia rather than for the domestic market. in

(C) Other cities and towns

Other Indus Civilization cities and towns include Chanhudaro, Kot Diji, Surkotda, Desalpur, Rojdi, Manda, Ropar, Kalibangan, Banawali, Balu, and Rakhi Shahpur.

(i) Chanhudara

(a) The ruined town of Chanhudaro, located 130 km south of Mohenjo Daro near Samarkand in Sindh, consists of a single mound divided into several parts by erosion. It is located in the left plains of the Indus, which flows about 20 km away. The site was discovered by N. G. Majumdar in 1931 and explored on a large scale by E. J. H. Mackay in 1935-36. The excavations have thrown light on the Harappan quarter and the post-Harappan culture at the site. Mackay reported another level of occupation below the water table and speculated that there may have been a pre-Harappan or Amrian culture. There was no major hiatus and the occupation continued even after the end of the Mature Harappan period.

(b) Available evidence clearly shows that it was a major center for the production of beautiful seals collected from a dozen or more Harappan sites. A large number of metal tools were also found that were used to cut the seals. Stocks of copper and bronze tools, castings, and evidence of crafts such as bead making, bone objects, bracelets, and other shell items and steel production, both finished and unfinished, indicate that Chanhudaro was mostly inhabited by artisans and an industrial town. The hasty evacuation of homes is also evidenced by the way objects were scattered. Excavations revealed a kiln with a brick floor, equipped with two doors, used for glazing small steatite beads. Two other important finds are a terracotta model of an ox cart and a bronze toy cart.

(ii) Kot Diji

(a) 50 kilometers east of Mohenjodaro, on the left bank of the Indus, today about 32 km from the river but still near one of its ancient flood channels and thus close to agriculturally productive land, is the site of Kot Diji. It is located on solid ground below a small rocky outcrop that is part of the limestone hills of the Rohri range. It was excavated by F.A. Khan between 1955 and 1957.

(b) Although pre- or early Harappan and mature Harappan levels have been found here, the most interesting aspect is the presence of a ‘mixed’ layer. This “mixed” stratum was suggested by the Mughals, but in Allchin’s view, it hardly indicates a transitional period. Two other sites, i.e. Nausharo (Jarrige 93) and Harappa (Meadow 1991), also showed a clear progression from early Harappan to mature through a transitional phase.

(c) The early Indus settlement was built on bedrock, while immediately above it was discovered floors of houses contained within a massive defensive wall fortified with bastions. The houses were made of stone and mud bricks. A small number of leaf-shaped arrowheads, stone querns, flower petals, corn crushers, and one fine terracotta bull were found. A fragment of a bronze bracelet is also presented.

(d) The early occupation of Kot Diji ends with evidence of two massive fires and is replaced by a mixed but largely advanced Harappan culture. Mature Kot Diji included a citadel and an outer city and other typical features: a well-ordered town plan with lanes, houses with stone foundations, and mud brick walls. The houses were spacious. The roofs were covered with reed mats, giving the impression of being plastered with mud. Storage vessels built on clay floors and large unbaked cooking ovens lined with bricks were also found. A broken steatite seal, several inscribed sherds, terracotta beads, semi-precious and etched carnelian beads, copper/bronze bracelets, metal tools and weapons (axe blades, chisels, and arrowheads), a terracotta bull, and five mother goddess figurines were also discovered. Indus pottery with its original bright red surface and compact texture has pipal leaves, intersecting circles, peacocks, antelopes, sun symbols, carved patterns, etc.

(iii) Surkotada

(a) Surkotada, located about 160 km northeast of Bhuj in Kutch, has emerged as an important fortified Indus settlement in that three stages of Harappan occupation are attested. The site was excavated by J.P. Joshi in 1972.

(b) The mound measures 160 m in length from north to south and 125 m in width. The Indus settlement at Surkotada began with a mudbrick and earthen clod fortification consisting of a citadel and residential outbuildings on a rectangular plan of approximately 130 × 65 m east and west as a major axis. The citadel was built on a raised platform of hard yellow rammed earth (1.50 m ht). The fortification was provided from the inside with rubble cladding with a basal width of approx. 7 m. It had two entrances on the south and east sides. In the last phase of this site, previously unknown horse bones were recorded. A cemetery with four-pot burials with several human bones was also found.

(iv) Desalpur

(a) Desalpur, situated near Gunthali in Nakhatrana taluka of Bhuj district (Gujarat) on the Bhadra river, excavated first by P. P. Pandya and M. A. Dhakey and later by K. V. Soundarrajan, has yielded remains of the Indus Civilization.

(b) Desalpur, during the Harappan age, was a fortified town built of dressed stones with mud filling inside. The houses were built close to the castle wall. In the center was found a building with massive walls and indented rooms. It must have been some important structure. The occupation continued in the post-Harappan period.

(v) Rojidi (Rojidi, Rozaidi)

The site lies about 2 km west of the present village and 50 km south of Rajkot on the left bank of the Bahadar or Bhadra river. Excavations at the site have provided evidence of Harappan settlement with adobe platforms and drains along with hornblende and agate weights, etched carnelian beads, agate, terracotta and faience copper objects, toys, inscribed sherds, and white microspheres. Like Desalpur, occupation continued during the post-Harappan period.

(vi) Manda

Located at a distance of about 28 km northwest of Jammu on the right bank of the river Chenab, a tributary of the Indus, at the foot of the Pir Panjal range, this site is the northernmost center of the Harappan civilization. Located in the ruined 18th-century Manda fort, this site shows the existence of adult Harappans living with pre-Harappan people. Excavations have yielded a triple sequence of cultures from the pre-Harappan to the Kushana period. Among the Harappan antiquities are a copper pin with a double spiral head (12.8 cm) believed to be of West Asian origin, inlaid bone arrowheads, bangles, terracotta cakes, shards with Harappan graffiti, devil blades, an unfinished seal, and several he sat. querns and mallets. A horizontal accumulation of large amounts of debris may indicate a fallen wall.

(vii) Rupar/Ropar (modern Roop Nagar)

Excavations at Ropar, located near the confluence of the Sutlej, about 25 km east of Bara (Punjab), yielded a fivefold sequence of cultures (Harappan, PGW, NBP, Kushana, Gupta, and Medieval). Incidentally, it was the first Harappan site to be excavated in India after independence. It was excavated by Y. D. Sharma (1955-65). Inhabitation began at the site before the Indus phase, as is evident from the discovery of a pottery tradition associated with Kalibangan-1 as a small settlement. In another sub-phase, Ropar developed into a town associated with the mature Indus civilization, as evidenced by typical Harappan pottery, blades, beads, faience ornaments, bronze celts, terracotta cakes and one inscribed steatite seal with typical Indian pictographs. Several oval pit burials were excavated in the northwest corner of the site, and one example of a rectangular adobe chamber was recorded. The grave goods contained 2 to 26 pots in various models. There were also some graves without any goods. They could have been the graves of middle or lower-class people. Faience and shell bangles, agate beads, copper rings, etc. were also found in the graves. The evidence of dog burial under human burial is very interesting in the Harappan context, not found anywhere else. However, this practice prevailed in Burzahom (Kashmir) during the Neolithic culture.

(viii) Kalibangan

(a) The site of Kalibangan (literally black bracelets) is located on the south bank of the now-dry Ghaggar River, about 200 km southeast of Harappa and 480 km east-northeast of Kot Diji. It is located in the Ganganagar district of Rajasthan. Its plan was similar in many ways to that of Harappa and Mohenjo Daro, though smaller than both. Like Harappa, it lay on the south bank of the river, with its orientation just as firmly north-south. Also, the plan of the Kalibangan citadel was clearly revealed, consisting of two almost identical rhombuses, separated from each other by a thick wall. Of the two, the northern section contained regular housing, while the southern section contained a series of mysterious brick platforms, possibly sacrificial scenes. The lower town had a regular network of streets, reminiscent of those of Mohenjodaro. In all these cases (Harappa, Mohenjodaro, and Kalibangan) there appeared to be regular size ratios between the various elements of the city plan: at Kalibangan the citadel is approximately 120 x 240 m, and the lower city 2000 x 400 m. At Mohenjodaro the equivalent figures were approximately 200 x 400 and 400 × 800 m, suggesting that the two larger cities were literally four times the size of the smaller ones (Allchins, 1997).

(b) One of the most interesting aspects of the excavations carried out by B.B. Lal and B.K. Thapar since 1959 was the fact that a Harappan city (12.5 hectares) was found to have been built over the remains of an early Harappan (4.5 hectares). ). Radiocarbon dates suggest a broad dating for Early Harappan from around 2900-2500 BC. The early Harappan settlement appears to have been surrounded by a mud brick wall and consisted of five construction phases.

(c) Excavations revealed the floor plan of a parallelogram citadel with well-arranged houses oriented roughly in the main direction. The average house consisted of a courtyard, several rooms, and cooking furnaces of underground and above-ground varieties. Excavations revealed evidence of a plowed field surface with grooves in two mutually perpendicular directions, knowledge of copper technology, the use of agate and chalcedony blades, and abundant remains of clay vessels with six different fabrics, shell bracelets, steatite disc beads, several of which continued into the subsequent Harappan cultural phase. Standardization of brick sizes appears to have already occurred during this early Harappan period, and although the ratio (3:1:1) differs from that of the mature period, it clearly indicates the way in which the early period anticipates what is to follow. A number of other features also anticipate the Maturity stage, such as the interior incised decoration on the bowls and the offering stands.

(d) Kalibangan in its mature stage like other Harappan cities was divided into two parts, the walled city (citadel) and the lower city. The citadel had the shape of a parallelogram (with dimensions of 240 x 120 m) with an east-west division forming two rhombuses with walls. The northern half of the citadel had residential buildings with limited development. The southern part of the citadel had adobe platforms with seven fire altars in a row. A well and several walkways appear to be related to washing and rituals. Evidence of a platform with a well and rectangular altars made of burnt bricks with the bones of cattle and deer testify to the fact that animal sacrifices were performed here. There were also fire altars in the lower city.

(e) The lower town at Kalibangan was also fortified (240 x 360 m). It was also planned like other Indus settlements. It had two gates and the northwest side gate was for riverside access. The average house in Kalibangan consisted of a courtyard with living rooms and a kitchen. The floors of the house were paved with rammed earth or adobe bricks. One of the houses had a floor of burnt bricks with carved intersecting circles. The use of burnt bricks in Kalibangan was found only in wells, bathing walkways, and drains.

(f) Steatite seals and terracotta seals were important writing materials. Seals indicate a reed impression, suggesting their use for packaging purposes. One seal has a deity on it. The cylinder seal was similar to its Mesopotamian counterpart. The discovery of the inscribed fragments suggests that the Indus script was written from right to left, as evidenced by the overlapping of the letters.

(g) Interestingly, Kalibangan has provided evidence of the oldest earthquake ever discovered through excavation, dating back to around 2600 BC. The plow field is also the oldest evidence from 2800 BC.

(h) The Harappan cemetery, located south of the dwelling, revealed three methods of disposal of the dead—rectangular grave pits; oblong/rectangular pits without carcasses; the largest urns with pots and grave goods without ashes and bones. The graves of the second type were those who died elsewhere and their graves were placed here only symbolically. Studying certain skeletons has revealed some interesting facts about disease. The baby’s skull revealed some interesting facts about diseases. The child’s skull revealed a case of hydrocephalus, and in an attempt to treat it three holes were pierced and certain marks were made with a heated instrument. This primitive practice, known as trephination, for treating headaches was also prevalent in Lothal and Burzahom. One skeleton revealed a sharp cut to the left knee, probably by a copper axe. The drying up of the Ghaggar seems to have led the Harappans of Kalibangan to abandon the settlement around 1700 BCE.

(ix) Banawali

(a) The Banawali Mound (15.5 hectares), covering an area of over 400 m2 and about 10 m high, is located on a rainwater drain, Rangoi, identified with the ancient bed of the Saraswati River in Hisar district, Haryana. Excavations carried out at the site by R. S. Bisht yielded remains of Pre-Indus (Early Harappan), Indus, and Post-Indus cultures.

(b) Phase II at Banawali belonged to the Harappan period, but there were significant deviations from the established norms of town planning, which believed in the general concept of a checkerboard or grid pattern. Roads are not always straight, nor are they cut at right angles, and residential sectors or blocks of flats only adapt to the orientation of nearby roads. It lacked a systematic drainage system – a notable feature of the Indus civilization. The image of a fortified city with an additional citadel inside is created, thus dividing the entire town into two parts, i.e. the citadel or inner fortress (acropolis) and the lower city. Each of the two divisions has huge defensive walls (5.40m to 7.50m) with entry points, an extensive road system, residential sectors as well as housing blocks, and functional drainage and sanitation facilities. The citadel was 215 m (or 215 + 20 m) along north-south with an east-west length of up to 75 m (or 75 + 7 m). Its walls were smoothly plastered with well-kneaded mud mixed with chaff and cow dung.

(c) The ‘Lower Town’ was divided by roads, lanes, and streets and their direction was belied by the ‘myth of planning grids’. The lanes were connected to two main roads, giving each house or block an independent identity. The plan of the rectangular “palace house” (52 x 46 m) was restored, with eleven units of rooms, large and small, except for small cubicles located on a thick wall. It has an open large courtyard, a living room, a bedroom, a toilet, a kitchen, and a prayer room, in addition to five cubicles. The discovery of a tiger seal in the living room and several others from the house and its surroundings, chert weights, lapis lazuli beads, and luxurious Harappan pottery indicate that the house belonged to a prominent merchant.

(d) The remains of material at Banawali are quite rich, including classical Indus pottery, a few steatite seals, and a few terracotta seals with typical Indus script. Other remains include gilded terracotta beads, lapis lazuli beads, etched carnelian, shells, bones, faience, steatite and clay beads, faience earrings in the shape of pipal leaves, clay bracelets, etc. The terracotta figurines include several mother-goddess figurines. The scales at Banawali recall Indu’s examples. Copper objects include arrowheads, spearheads, broken sickle blades, razors, chisels, rings, double spiral and single pins, ear and nose rings, and fish hooks.

(e) Among other important antiquities, we have a clay model of a plow, which appears to be a genuine prototype. It is a combined form of beam and shoe. The beam is curved like an inverted ‘s’ with a hole at the top end. The tip of the shoe is sharp. Its elongated back is pierced with a vertical opening to accept a curved or vertical handle. In addition, the excavators also collected a few plow fragments. A unique feature of planning, not yet found in any of the Indus sites with defensive works, was the exposure of a deep and wide ditch outside the city walls and a wide corner between them. Another significant find may be the discovery of an elaborate gate complex, which was equipped with a front ditch, side bastions, and a built-in 8 m wide passage with a large longitudinal drainage, a width retaining wall, and a flight of steps leading to the southern bastion.

(f) Banawali produced certain interesting terracotta models of wheels, both spoked and fixed, known to the Vedic Aryans as Sara chakra and pradhi chakra. One of the houses contained many seals and weights and may have belonged to a merchant. In addition, his toilet was equipped with a basin located on an elevated spot in the corner near the drain, which drained the wastewater into a septic tank located outside the street. However, of great interest was the discovery of an “assay stone bearing gold streaks of various shades,” indicating that the practice of gold testing was present during the Harappan period.

(x) Kunal

(a) Located in Tehsil Ratia of Hisar district, Haryana, on the banks of the now dry Saraswati river, this 3-acre settlement has been excavated by J. S. Khatri and M. Acharya since 1986. onwards. According to the excavations, the site has left an archaeological record of the process of change that led to the emergence of the Harappan culture. People began to live here after the artificial increase of the land by 0.71 m. A dwelling consisting of two units was found – one circular and a waste pit adjacent to it. The dwellings were the “pit-dwelling type” also known as the semi-underground type. This phase of buildings represents the Early Harappan phase and the IC period represents a transitional phase between the Early Harappan and Mature Harappan culture complexes.

(b) Dwellings changed from semi-subterranean huts to regular square rectangular houses built of typified mud bricks. The sizes of the bricks are in two ratios 1:2:3 and 1:2:4 (9x 18 x 36 cm; 11 x 44 cm; 13 x 26 x 39 cm; 11 x 22 x 33 cm), both are used at the same time. It is generally believed that the former was adopted by the Sothi-Kot Diji people and the latter was adopted by the Mature Harappans. Bricks 1; The ratios of If (1, 2): 3 create a perfect “English bond”, a property that creates the greatest strength of the structure and protects it from breaking into blocks. This place was characterized by a developed drainage system.

(c) In one of the rectangular brick houses, the excavators found a virtual hoard of gold and silver ornaments set in a silver sheet and buried in a simple red spherical pot of early Harappan fabric. The silver objects include two diadems, one small and one large, each with a large fully open flower with petals ending in an ornament like the Greek letter alpha. One large silver bracelet with horizontal bars was also found. In another house of the same period, a large number of gold ornaments were found with disk beads, bowl-shaped beads, round sheet beads with facets all over, etc. In a few houses, terracotta beads are found, but they are of the same shape as the metal ones. Finds include faience and carnelian beads and blades. Copper objects include coiled finger rings, coiled cones, inverted V-shaped arrowheads, flat axes, fishhooks, spearheads, etc. A terracotta cup with molten metal still adhering to the inner surface came to light. Similarly, one potter’s kiln came to light. Six steatites and one seal were found.

Conclusion

Harappan towns and cities were part of the ancient Indus Valley civilization, thriving in present-day Pakistan and northwest India. Notable sites include Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, and Dholavira. These cities exhibited advanced urban planning, with well-organized grid layouts, multi-story buildings, and an intricate drainage system. The people of the Harappan civilization engaged in trade, as evidenced by their artifacts found in distant regions. The script (Indus script) used by the Harappans remains undeciphered, contributing to the mystery surrounding their culture. The decline of the Indus civilization is still not fully understood, with factors like environmental changes and possible invasions being considered.

Videos about Important Towns and Cities of the Indus Civilization

(FAQ) Questions and Answers about Important Towns and Cities of the Indus Civilization

Q-1. What were the main cities of the Indus Valley Civilization?

Ans. The major cities of the Indus Valley Civilization included Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Lothal, Kalibangan, and Dholavira.

Q-2. Where were these cities located geographically?

Ans. The cities were located in what is now Pakistan and northwestern India.

Q-3. What was the significance of Harappa and Mohenjodaro?

Ans. Harappa and Mohenjo-daro were major urban centers that featured advanced urban planning, drainage systems, and standardized brick construction.

Q-4. Were these cities contemporary with ancient Mesopotamian civilizations?

Ans. Yes, the Indus Valley Civilization existed around the same time as the Mesopotamian Civilizations, with some cultural interactions.

Q-5. What archaeological discoveries were made in these cities?

Ans: Archaeologists have found well-planned cities, advanced drainage systems, standardized weights and measures, pottery, seals, and evidence of trade.

Q-6. Why did the Indus Valley civilization decline?

Ans. The exact reasons for the decline are uncertain, but factors such as environmental changes, natural disasters, and changes in the structure of trade are thought to be possible contributors.