Hinduism and the Caste System Explained an ancient social structure that profoundly influenced Indian society. This meta-description invites exploration of the historical origins of the caste system, its incorporation into Hindu philosophy, and its impact on social dynamics.

Although not intrinsic to Hinduism, the caste system has been intertwined with religion for centuries, shaping social hierarchies and influencing interactions. Discover how modern perspectives and movements challenge and develop this traditional system, and explore the intricate interplay between religion, culture, and social structures in the context of Hinduism and the caste system.

Hinduism and The Caste System Explained

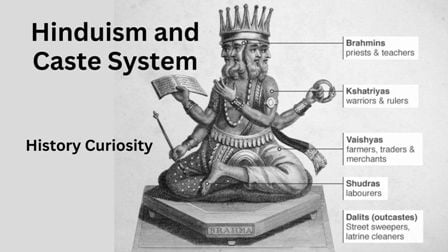

| Historical Facts | Hinduism and The Caste System Explained |

| Brahmins | Priests, scholars, and teachers |

| Kshatriyas | Warriors, rulers, and administrators |

| Vaishyas | Merchants, farmers, and business professionals |

| Shudras | Laborers and service providers |

| Dalits (Untouchables) | Historically marginalized, often performing tasks considered impure |

Introduction

“Hinduism” and “caste” are paradigmatic examples of one great paradox that haunts the social sciences dealing with the Indian field. However, it is crucial to our understanding of Indian social and cultural reality that none of these words, which we can reasonably assume are among the most used in academic literature, can be accurately translated into the Indian language. What is at stake, then, is how to define exactly what we mean when we use the terms “Hinduism” and “caste” and how the two terms are related to each other. Is the caste system Hindu? Is Hinduism necessary for the caste system to exist? Is Hinduism primarily dependent on this one organization? And would Hinduism inevitably disappear “if and when caste disappears,” as Srinivas also argued (Srivivas, 1956)? Is there such a thing as casteless Hinduism? In other words: to what extent are Hinduism and caste the same?

Beyond the misguided notions of Hinduism as a homogenous category, a “religion” shared by about 80 percent of India’s population, one must bear in mind the diversity of Hindu practices and representations.

Along with other criteria such as sectarian or regional traditions, caste affiliations are central to structural diversity in Hinduism. The need to unify such heterogeneity under a unique term and category has only grown relatively recently, reinforced by colonization and the struggle for independence and nationalists (Sontheimer and Kulke, 1989; Lorenzen, 1999), without radically undermining either the diversity between castes or the supreme importance of the caste system in Indian social structures, daily life and religious practices.

Caste, Hinduism and Society Explained

Most studies of Hindu caste rightly begin with a distinction between varnas and jatis. On the one hand, castes like varnas divide society into four orders: Brahmins (religious specialists), Kshatriyas (rulers and warriors), Vaishyas (farmers and traders), and Shudras (servants). Such a concept of caste as varna is inherited from Brahmanical ideology. On the other hand, castes like jatis divide society into thousands of inherited, endogamous social groups, a concept close to the naturalistic concept of species. Castes as varnas illustrate the intrinsic socio-religious dimension of Hinduism. Not only does the ability to perform certain rituals and be initiated depend on the varna, but such a religious hierarchy corresponds to a social role embedded in a truly organic vision of society. The founding myth of the varnas originates from the dismemberment of the primordial being (Purusha). Rig Veda Hymn X/ 90: Brahmins are the mouth, Kshatriyas the arms, Vaishyas the thighs and Shudras the feet.

Along with such social structuring supported by the caste system, another dimension of varnas represents the Hindu model of interaction between individual life and society.

Hindu ideology, best formalized in the Bhagavad Gita’s teachings of Krishna Arjuna, requires individuals to uphold cosmic order by adhering to their own, individual dharma, varying according to varna. Kshatriyas should eat meat and wage war, while Brahmins should be nonviolent vegetarians devoted to the ritual maintenance of cosmic order. In stark contrast to any universal morality, the varna system finds Hinduism as a structuring model that dictates to each individual his distinct place and duty in the cosmos and society.

Such holism could argue in favor of a supposedly non-segregative Hindu society where each varna is necessary and complementary to the others, just as the human body needs all its members. In this perspective, emphasizing how Hinduism inevitably goes with casteism is often assimilated to a hidden strategy to divide the so-called Hindu community, to weaken its reflexes of solidarity in communal contexts. But the “naive” understanding of castes as harmoniously complementary clearly lacks a hierarchy of governing systems and shared representations that regard the head (Brahmins) as the noblest part of the body and the feet (Shudras) as highly impure.

Relative purity or caste system based on Hindu ritual ideology

If the varnas are structured by their relative access to sacrifices, the hierarchy also relates to Hindu notions of ritual purity and pollution.

A Shudra is not pure enough to pass through them. the upanayanam (sacred thread) initiation ceremony and becoming a twice-born dvija (a category reserved for the three upper varnas). But the relative purity structuring the Hindu caste system is best illustrated by the daily life governed by the subtle hierarchy of the jatis. Not only is each individual born in a particular jati, not only does he marry and die in it, but the jati begins to govern his day-to-day interactions.

The ancient regulation of the necessary distance (the number of steps Herrenschmidt, 1978) to be respected between a Brahmin and a low-caste individual was replaced by the prohibition of physical contact, commensality, and exogamy.

As a result, the higher one stands in the caste hierarchy, the higher the risk of pollution and consequent measures and taboos. Castes like jatis are a relational system. The internal quality (guna) of each jati is highly transferable, primarily through the cooking (and serving) of food, water, and bodily fluids (semen, saliva, sweat, feces).

The purity-centered identity of the Jatis is also linked to professional activities that, although not necessarily respected today, still retain their value as indicators of cleanliness: the Jatis whose traditional occupation was the treatment of leather (tanner Jatis) or hair (barber Jatis ), still suffering. from polluting stigma. Focusing on individual relationships and transmissions of quality, Hindu sacrifice has been studied through the transactional approach of caste. Payment to the ritual specialist can be seen as a transfer of inauspiciousness from the individual patron (who benefits from and pays for the ritual) to the ritual specialist who needs constant provision and purification.

Accordingly, one must not be misled by the Brahminical understanding of caste as varna, which places the Brahminical archetypal profession of ritual specialist at the top of the social hierarchy.

Brahmins are far from a unified brewing community, and the main criterion governing the hierarchy among them is precisely public ritual service. Working in a public temple for a Brahmin does indeed mean enjoying the closest access to divinity, but it also means ministering to clients of varying status, resulting in lower prestige than other Brahmins without ritual duties. And when in charge of highly impure ritual activities, a Brahmin specialist may even be “treated as an Untouchable”, such as the funeral priests officiating in Banaras.

This relational dimension of the caste system goes hand in hand with a certain flexibility depending on individual or collective strategies. The system’s flexibility builds on a long history of jati merging or splitting dynamics accompanied by adjustments at the level of ritual traditions that each new jati chooses to follow.

The key issues are again relational: more than “what can I eat?”, the question raised is “with whom can I eat?” and /p. 238/ ‘who cooks what I eat?’ While most everyday prohibitions are unavoidable in public, many are relaxed in private settings, a point that counts for the global loosening of caste rules in urban contexts. Moreover, even the most polluting activities can be justified in the interest of the whole system.

According to this apaddharma, a caste rule that one must follow in times of crisis, even a Brahmin individual is allowed (even required) to eat dog meat in case of extreme starvation to avoid the greatest loss: the death of Brahmins and the consequent inability to maintain a holistic caste system. Other solutions to disregarding caste prohibitions are rooted in the Hindu logic of ritual purification.

Specific rituals (for example, dana-dar, purification bath, head shaving, or recitation of japa mantra) and pilgrimage (tirthayatra) are expiatory rituals (prayacita) that enable the correction of most caste problems.

Caste in Hindu temples and villages

Ritual practices link caste to Hinduism through a complex relational ideology of purity. Varna logic falsely assumes that Brahmins have a monopoly on priestly functions, notwithstanding the many lower-caste ritualistic specialists who serve everywhere in Indian Hindu homes, shrines, and ceremonies. In fact, Hindu ritual traditions vary widely by caste, and Hindu mythology and pantheon are permeated with caste considerations.

A kind of ritual division of labor connects Hindu deities and castes: a brahmin individual can be induced to turn to a low-caste ritual specialist, for example, when faced with a danger identified with a spirit that only an exorcist can deal with. If ritual activities differ between upper and lower castes, they may also complement each other when, for example, Dalits are traditionally required to beat drums during funeral processions.

But on the other hand, complementarity is challenged by those who live it as segregation and choose to protest by renouncing their traditional caste ritual attributes.

In Hindu temples, social hierarchies based on criteria of contact, distance, and consumption govern both spatial organization and rules of ritual precedence. In addition to prohibiting Untouchables from entering high-caste premises, Hindu temples replicate caste hierarchy and pollution rules through concentric circles (from the garbhagriha to the mandapa and surrounding areas) that restrict deity access by caste.

The enjoyment of prasad (the remains of the gods from sacrifices) may also be reserved for the upper castes or distributed in a certain order. Apart from the temples, Hindu castes and religious practices are jointly rooted in the village territory.

Spatial organization by caste in village India is still largely governed by local religious topography.

Most village Hindu temples follow caste lines (or groups of assimilated castes): they are located in a caste-specific district whose caste members usually look after the devotees, the local priest and the leading patrons. But the village caste system should also be studied through the relational network linking each individual god, temple and community with those of other (caste-specific) neighbourhoods.

Religious circulations such as processions typically recreate socio-spatial dynamics and sacralize caste neighborhoods as divine jurisdictions – the kshetra. Various village rituals express the sociological unity of the village, and ritual changes typically accompany new adjustments in village intercaste relations. It is true that with economic changes since several decades and Brahmins widely leaving the villages, some Shudras have become locally dominant castes.

However, we should not conclude that the Hindu ritual hierarchy has completely disappeared. The influence of Hindu ideology in everyday caste matters is still pervasive in the village spatial segregation of the former Untouchables (“those who cannot be touched”). Most of the other permanent prohibitions (the right to use the village cremation ground or the village well) and the most common humiliating punishments for non-compliant lower caste individuals (having one’s shoes on one’s head) restore ritual criteria.

How caste issues interact with the definition of Hinduism

As a historically contingent category, Hinduism has been continually redefined according to its relations with caste, moving from being synonymous with Brahmanism (when an Orientalist perspective excludes lower caste practices and representations from the realm of “Hinduism”) to an inclusive continuum of heterogeneous traditions.

Strictly speaking, apart from being segregated as polluting individuals, Dalits are casteless as varnas (they are avarnas), a notion that has long kept them outside of Hinduism. Even today, Dalit activists regularly use the phrase “caste Hindus” to refer to people with varnas (savarna).

It also places the “world of caste” in opposition to non-Hindu tribal groups, a dichotomy re-materialized by British administrators and their Brahmin sources.

But the political stakes behind defining the boundaries of Hinduism also contributed to the strategic inclusion of groups previously considered non-Hindu. During the mobilization for independence in the 19th century, the need for a unifying category against the British and a position against other religions for census and electoral purposes gradually led to the incorporation of lower castes into the Hindu community.

But the outcome of Hindu consciousness among Dalits remains debatable. Viramma, an outcast woman whose life story vividly acknowledges the subjective experience of the lower castes, hesitates as she articulates Untouchability and Hinduism: “Who are Hindus, Muslims, Christians, that, I don’t know for sure, must be Hindus? of caste. Wait, I think I heard that once: Hindus, it’s us, the poor, who call ourselves that in speeches.

If politically motivated processes of inclusion favored understandings of Hinduism shared by savarnas and avarnas, they also restored caste hierarchy and segregation as central to Hinduism.

The national debate over the ban on Untouchables from entering government-run Hindu temples has long sparked sometimes violent opposition from upper castes. When the police forced Varanasi Brahmins to let untouchables enter the Vishwanath temple in 1956, the local orthodox Hindus decided that such a problem was polluting the Shiva linga and decided to build another, private, “New Vishwanath Temple.” And when, in 1936,

Gandhi inaugurated the Banaras Bharat Mata (Mother India) mandir, a temple/museum with a marble map of India standing in place of the main deity’s murti, he attempted to express national unity and egalitarian Hinduism across borders. caste division: “There is no statue of gods or goddesses in this temple. I hope that this temple will act as a universal platform for all religions as well as Harijan (untouchables) and for all castes and creeds and will contribute to feelings of religious unity, peace and love in this country.

However, Gandhian ecumenism does not challenge the caste hierarchy and its Hindu ritual criteria of purity: during the inauguration of the Bharat Mata temple, the so-called “sons of God” (harijans) were given bars of soap to “wash” themselves before being allowed to share a communal meal with other attendees. The anecdote reveals the deep discomfort of Western Indian nationalist elites with the ritually sanctioned caste hierarchy.

Moreover, such a focus on caste as an all-encompassing system, ambiguously linked to tolerance as a supposedly Hindu virtue, often returns to reinforce the equation between Hinduism and Brahmanism. Hence the sanskritization strategy implemented by those fighting against caste segregation within Hinduism: they typically follow the Brahmanical hierarchy, giving up the “impure” practices of the lower caste (blood sacrifice, meat and alcohol sacrifices, trance) to embrace the “pure” traditions of the higher caste. (vegetarianism), so he hoped to be granted a higher status.

Caste, Supremacy and Conversion

The focus on the Hindu ritual ideology of purity and pollution as a major dimension of the caste system and Indian society, as in Dumont’s (1966) influential theory, has been criticized as a Brahminical bias. Following McKim Marriott’s (1959) first counter-model, which emphasized issues of rank rather than purity, recent studies have looked at caste in terms of power and dominance.

They argue in favor of a more horizontal reading of caste, insisting on non-religious dimensions such as socio-political subordination or empowerment and electoral lobbying. Such analyses favor castes as bounded communities with relationships and hierarchies focused on access to resources and power that are unfettered by ritual ideology or Hinduism per se.

Again contrasting the argument of intrinsically Hindu ideology, subaltern studies also argued in favor of an originally much more flexible system, which was only cemented in colonial times by British taxonomic obsession and divide-and-rule strategies.

Indeed, representations of the caste system and its relationship with Hinduism evolved greatly during this period, including the manipulations of independent leaders eager to assert a Hindu majority by including Dalits in this category. After independence, it was once assumed that the Hindu socio-ritual caste system would inevitably disappear with the advent of modernity, globalization and urbanization.

Although caste rules are more restrictive in villages (still the vast majority of India’s population), such a hypothesis has long been abandoned. Castes have proven perfectly compatible with social classes: these two different logics somehow come together, with social handicaps (poverty, poor access to health or education) often associated with ritual lower statuses. In order to combat such segregation, the quota reservation system was also instrumental in the resilience of caste consciousness and in the legal definition of caste limited to Hindus (for example, quotas do not include Christian other backward classes).

One of the strongest illustrations of India’s assimilation of complex caste relations to Hinduism lies in the fact that many castes fighting against their segregation eventually chose to convert to Islam, Buddhism, or Christianity.

The escape of castes through the abandonment of Hinduism seems to confirm that casteless Hinduism cannot exist. Such a perception of how the caste system derives directly from Hinduism and the Hindu nature of low-caste oppression eventually led the “Father of the Indian Constitution” Ambedkar to convert to Buddhism, thirty years after he publicly burned (in 1927) the Laws of Manu, the text Dharmashastra in which the sage Manu reveals the rules of caste.

The existence of castes outside Hindu communities is meant to support the so-called Hindu reading of India through Dumontian theory. Nevertheless, it must be remembered that such (individual or rather collective) conversions rarely end segregation.

In fact, if the jati hierarchy is flexible and has never been written down for eternity, it remains a matter of relationship, depending on how others. assess your relative purity and then engage with you daily. Indeed, neither Indian Christianity nor Indian Islam can be understood without looking closely at their internal caste relations and hierarchies and their relations with the Hindu castes.

Hardly changing such relational prospects, cases of conversion highlight how non-Hindu religions have never been able to transcend the supremacy of caste. For example, Indian Catholicism replicated caste hierarchies even as it fought against the religious sanctions structuring the caste system, and also contributed to the development of a language for social disputes.

Moreover, when a section of the caste converts to Catholicism. For example, inter-religious marriages do happen, but only as long as caste endogamy prevails. Apart from the (ritual-religious or political) focus chosen to solve caste problems, caste stands at the intersection of different classification systems (referring to religious or kinship terminologies and structures) and different systems of dominance. Hence the sometimes confusing identities.

If hijra individuals are first defined by their gender (transsexual) identity, they are also Hindu or Muslim and may come from higher or lower castes.

Adding a high-caste patronymic to one’s name is a common strategy to support the rising claims of one’s family or community without challenging the caste system. An individual of the Jat caste may be Hindu, Sikh or Muslim; a member of the lower castes and a member of the locally dominant class and caste.

Hinduism without caste? Challenges of Caste in Hinduism

Apart from the lower castes fighting against the hierarchy of the system, the logic of caste is first challenged in Hinduism itself through ascetic individuals and institutions. The caste system has been studied as grounded in a dialectical relationship between the world of caste, those householders who engage in actions according to their relative dharma (varnashrama dharma), and the renunciation of those ascetic individuals who renounce not only worldly possessions but the entire world of caste. Although in a sense the paradigmatic Hindus are dead to their caste: they have performed their own death ritual, freed from its rules and obligations, away from the otherwise inevitable fruits of actions and rituals With renunciation comes a challenge to necessity itself. caste for the existence of Hinduism.

Even if only temporarily and as a theoretical model, an ever-increasing number of Hindu pilgrims are replicating the quest for salvation apart from the world of caste and engaging in a casteless devotional experience. In line with Turner’s communitas model, the ideal experience of the Hindu pilgrim is truly egalitarian and frees pilgrims from sociological categories and constraints. However, ethnographic data on the actual experiences of pilgrims show that this ideal, indeed central to pilgrims’ self-images, is hardly consistent with the day-to-day organization of pilgrimages. Pilgrims usually travel with their relatives or villagers, so it is difficult to go beyond caste matters.

In addition, they are usually housed and ritually led by pilgrim priests (Panda) who maintain hereditary patronage relationships (jajmani) with their fellow castes for generations, ensuring that the basic rules of interaction and commensal rules are still respected during the pilgrimage.

Although the type of priest a pilgrim chooses increasingly depends on market rules, pilgrim groups remain rather homogenous in terms of caste status. Bhakti, a powerful caste competition in its own right, is another link supporting Hindu pilgrimage. Devotional (bhakti) traditions, beginning around the 5th century AD, regularly promoted anti-Brahmanic ideologies. Focused on the monopoly of ritual, the technical mediation of the Brahmins, the Bhakti movement argued in favor of an unmediated, emotional relationship with the divine.

In stark contrast to the varna theory, Hindu bhakti establishes the “universal” possibility of attaining god and salvation regardless of caste. Such a shift towards universality can also be seen in most modern sectarian traditions based on individual gurus and lineages, which often replace, in theory if not in practice, caste-based ritualism with casteless individual devotion.

From the Arya Samaj of the 19th century to contemporary guru-led sectarian movements, casteless Hinduism is often associated with the promotion of Indian unity around a Hindu nationalist ideology, bringing back the potential caste rivalry within Hinduism, again understood as all-inclusive and relevant to both social and religious matters.

Resilience of caste in overseas Hindu communities

One of the most fundamental challenges to the caste system and concerns about its association with Hinduism lay in its outcome in India’s overseas communities, an issue that crystallized academic interest soon after Indian diaspora. studies first developed.

The questions raised were threefold: first, the possibility or transformation of Hinduism when it leaves its Indian motherland; second, the resilience of the holistic caste system when only some individual castes are exported;

thirdly, on the possible emergence of a casteless Hinduism. In the late 19th century, Bengal witnessed a major debate about the consequences faced by high-caste Hindus leaving India’s sacred land (dharma-bhumi) and crossing the dark waters of the ocean (kalapani) to study, work or fight in far-off lands. Risking exclusion from their caste, such individuals specifically experimented with the possibility of being Hindu in a context where it was no longer possible to respect India’s caste system and regulations. For (mainly low-caste) Hindu laborers hired to work in sugar colonies in the Caribbean, Indian Ocean, or Pacific in the second half of the 19th century, two major challenges to caste persistence are generally highlighted: unchecked commensality and promiscuity across caste barriers during ship. passage and violation of the rules of purity governing endogamy, residence, and occupational specialization after installation in the colony. Most studies conclude that while castes still exist in today’s diaspora-installed or indentured labor communities, the caste system, structured by an ideology of purity, has weakened or even disintegrated in favor of a common Brahminization and ethnicization of the system. Interestingly, along with emphasizing the disappearance of matters of purity that guide most everyday interactions, few of these studies would question the durability of caste rules regarding marriage and sometimes commensality and ritual matters.

Diaspora studies thus opens the door to the possible compatibility of castes with overseas Hinduism. Dumont’s interpretation of the caste system as founded by Hindu ritual ideology has been the target of most alternative studies of caste insisting on non-religious (non-Hindu) dimensions in a sometimes too radical swing of the pendulum. It may be fair to say that half a century after Dumont’s Homo Hierarchicus, caste as a Hindu system originally born of Brahmanical socio-ritual ideology, but permeating Indian society far beyond the upper castes, still remains the main, if not exclusive, entry point into Indian society .

As a final attempt, let us answer our original inquiry and argue that caste and Hinduism are indeed largely identical. On the one hand, except in marginal or dialectical contexts (renunciation), castelessness in mainstream Hinduism is limited to ideological theories (bhakti) and attempts (sects) are often at odds with actual practices (sects, pilgrimage). On the other hand, caste in India cannot be considered without Hinduism, as caste hierarchies, daily practices and social rules are directly rooted in the overarching, inextricably social and ritual Hindu ideology.

Conclusion

Certainly not the only category relevant to the anthropology of Hinduism and the sociology of India, caste remains a crucial issue because the system is as pervasive as it is flexible, capable of transformation and adaptation to new contexts. It is not surprising, then, that castes managed to establish themselves at the very core of Indian society but also grew beyond both Hinduism (see castes in Indian Islam or Christianity) and religious matters (see social competitive movements and caste-based political agitation ) and outside Indian territory and society (see diasporic contexts). Rather than denying the fact that caste is integral to Hinduism, such expansions of the caste realm confirm the continuing relevance of the religious dimension of caste, since all the new caste avatars have indeed maintained a fundamental tenet of Hindu ritual ideology: the distinction between pure and impure.

(FAQ) Questions and Answers about Hinduism and the Caste System Explained

Q-1. What is the caste system in Hinduism?

Ans. The caste system is a social hierarchy prevalent in Hindu society that divides people into four main varnas: Brahmins (priests and scholars), Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers), Vaishyas (traders and farmers), and Shudras (laborers).

Q-2. Is the caste system mentioned in Hindu scriptures?

Ans. Yes, this concept has its roots in ancient Hindu scriptures, especially the Vedas. Manusmriti, a legal text, provides guidelines for social order and reinforces the caste structure.

Q-3. Can one change one’s caste in Hinduism?

Ans. Traditionally, caste was hereditary, and its change was rare. However, modern India has statutory provisions for affirmative action and social mobility, allowing for reservations in education and employment.

Q-4. Does the caste system still exist today?

Ans. Yes, even though the caste system is officially abolished in India, it still affects social dynamics and, to some extent, individual opportunities. Efforts to eradicate discrimination and promote equality continue.

Q-5. Are all Hindus part of the caste system?

Ans. Not all Hindus strictly follow the caste system. Urbanization, education, and social change have led to a more fluid social structure, and many people reject discrimination based on caste.

Q-6. How does the caste system affect everyday life?

Ans. The caste system can affect marriage, occupation, and social interactions. Discrimination based on caste, known as untouchability, has been banned by law but may persist in some areas.

Q-7. Is there a criticism of the caste system?

Ans. Yes, critics say the caste system perpetuates inequality and social injustice. Efforts to address these issues include legal reforms, affirmative action, and educational initiatives.

Q-8. What role does caste play in politics in India?

Ans. Caste continues to influence politics in India, with political parties often considering caste demographics in their strategies. Reservation policies aim to address historical injustices and promote the representation of marginalized castes.

Q-9. How does the caste system relate to the spiritual teachings of Hinduism?

Ans. Hindu spiritual teachings emphasize the idea of karma and dharma rather than a rigid social hierarchy. Some argue that the origins of the caste system are sociocultural rather than inherently religious.

Q-10. Are there efforts to eliminate the caste system?

Ans. Yes, various social and government initiatives aim to eliminate caste-based discrimination. Education, awareness, and legal measures contribute to the promotion of equality and social peace.